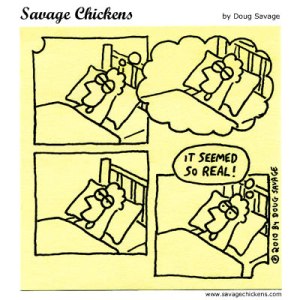

“Quantum mechanics is magic.”–Daniel Greenberger.

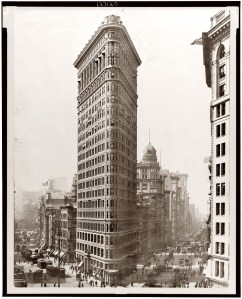

Image credit: Matthias Giesen http://matthiasgiesen.wordpress.com

Quantum mechanics. Niels Bohr said if you’re not shocked by it, you don’t understand it. Richard Feynman said nobody understands it. Albert Einstein said god does not play dice. Stephen Hawking said god does play dice and sometimes he hides the results. I say who the hell cares, as long as they give me fodder for my blog. Or my wife’s horse. Or my accountant’s newt. It all fills space, thus proving the vacuum is not empty. Isn’t physics fun? [Note: vacuum is one of the few words in the English language containing “uu.” But it’s not as cool as muumuu, duumvir or menstruum, proving that linguistics is fun, too.]