I Conjecture: The Concept of Infinity Could not Exist in a Finite Universe.

Part Three: Human Imagination

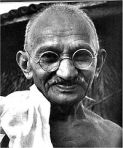

“Two things are infinite: the universe and human stupidity; and I’m not sure about the universe.”

― Albert Einstein

It is certainly understandable how somebody as brilliant as Einstein could perceive the rest of us to be infinitely stupid. Jokes about lawyers and politicians aside, I’m not sure about either. I remain an agnostic on untestable scientific  conjectures, as well as on religion. But my gut continues to tell me that my conjecture of infinity has merit, so I’ll proffer one final discussion before moving on to the next one.

conjectures, as well as on religion. But my gut continues to tell me that my conjecture of infinity has merit, so I’ll proffer one final discussion before moving on to the next one.

Nothing is inherently more self-contradictory than infinity. We can imagine it mathematically, but can’t measure it. We can imagine–sort of–infinite time and space. But physicists and philosophers tell us there are a finite number of possible combinations of matter and energy, at least in our observable universe with our laws of physics. But we can imagine things beyond those laws (fantasies like Harry Potter, various science fiction scenarios, and possibly real alternate universes with different laws of physics, to name just a few). So our imagination does not seem to be limited by what is possible or observable in nature. By that it would be reasonable to assume that human creativity and human stupidity are both potentially infinite.**

One of my favorite quotes about the universe is the famous J.B.S. Haldane proposition, “I suppose the universe is not only queerer (sic) then we imagine, it is queerer than we can imagine.” This would seem to be a contradiction of the notion that human imagination is infinite. David Deutsch says as much in The Beginning of Infinity, and he says so specifically in regard to this quote. His point is that human imagination and creativity are potentially infinite and that Haldane is, therefore, wrong. But where infinity is concerned, even Deutsch contradicts himself. For as he points out elsewhere in the book, there are mutually exclusive infinities and there are also larger and smaller infinities. Consider the set of all even integers and the set of all odd integers. They are mutually exclusive yet both infinite. Now consider the set of all even integers and the set of all integers. They are both infinite, yet the latter is twice as large as the former. The point is: there might be both an infinity of things we can imagine, and an infinity of things we can’t imagine. Deutsch himself indirectly alludes to this in his earlier book, The Fabric of Reality.

There is no question that the Haldane quote was true at least in the early part of the 20th century when he first espoused it. The universe certainly turned out to be stranger than anyone could imagine at that time. But the universe continues to surprise us, no matter what we imagine. And if our imagination is only potentially infinite we cannot imagine, at any one time, everything that exists or the larger infinity that might exist. To me, this is what makes the combination of human imagination with empirical knowledge so exciting. No matter what we can test or what we can imagine, there are still surprises out there to delight and confound us. But in my final analysis–the one that needs explanations and not just measurement–Einstein was absolutely right in another of his famous quotes:

“Imagination is more important than knowledge.”

Up next (after a few digressions and ridiculous timeouts): The conjecture of inevitability

**By potentially unlimited here, I mean no theoretical limit. To be actually infinite, humanity would have to exist forever.